WebAIM – dość popularna, niekomercyjna amerykańska organizacja zajmująca dostępnością serwisów WWW, opublikowała wyniki corocznej ankiety, przeprowadzonej na grupie 1245 użytkowników wykorzystujących oprogramowanie czytające zawartość ekranu.

Trzy najbardziej interesujące fakty:

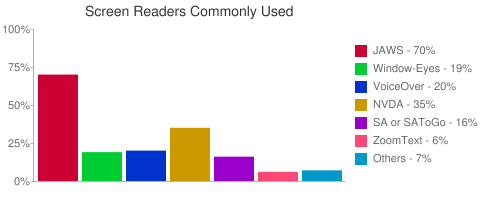

1. Najbardziej popularnym czytnikiem jest JAWS mający prawie 70% rynku

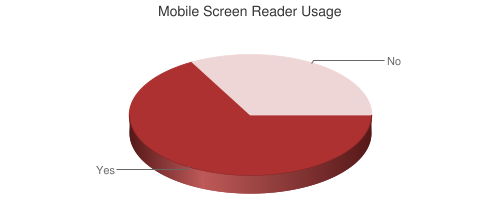

2. Dwie trzecie ankietowanych, stwierdziło że używa screen readerów dla na urządzeniach mobilnych

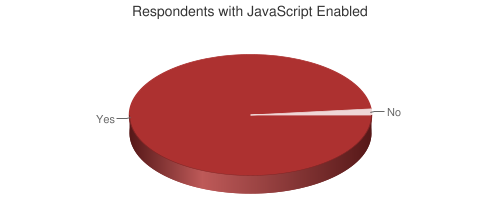

3. 98% użytkowników oprogramowania do czytania z ekranu używa JavaScriptu

Pozostałe, równie interesujące informacje (m.in. związane z social media, polami long desc i odnośnikami “Skocz do”) znajdują się na stronie projektu.

Recent Comments